A while back, I had a child come and join my dayhome. Over the first few weeks of care, I observed their tendency to seek control: they would gather toys and not allow other children access to them; they would quickly shift blame from themselves to others; they would run away from me or get stuck in a ‘defiant’ sort of headspace when I needed to hold even a simple boundary. It was very difficult for this child to play cooperatively; they were quick to shoot down the ideas of other children, which led to frustration for everyone. I also observed that they really had a tough time accessing their own inner voice and creativity, whether that related to coming up with a character to role play or creating art or what they wanted to do next.

But mostly, I sensed that this child was constantly ‘on guard,’ never knowing if I would punish them when an accident happened or they upset another child.

I really struggled to manage the behaviours that were coming up. So I chatted with the parent about what I had been seeing, and they described being at the end of their rope. As I gently probed further, they shared that they didn’t know how to use consequences to change behaviour anymore, that even taking away a prized possession like a gaming device or special toy didn’t seem to work. Their child would simply say, “Fine, take it away. Put it up. I don’t care.” And the behaviour would continue—often worse than before.

At some point in my journey, I remember having an A-HA moment about control and power struggles. As children get older, they are going to have more power and agency in their lives, and if I wanted to use my power over them to control their actions, I would need to continually up the ante to always be above them on the power ladder. Some children will submit to this way of managing behaviours—I, myself, being one of them—while other children are more likely to fight back—I sensed this child was the latter. They are not able to put into words why they think something is unfair or hurtful, and so their behaviours tell their story. Whether it’s yelling, hiding, hitting, controlling, or ignoring directions, they are fighting to be heard, to be witnessed, to know that their voice matters. I love these children as much as I’m challenged by them; they call out an unjust system and force me to reckon with the way I treat those who have less power than me. At some point, using dominance over these children will no longer have the intended effect (although, it certainly has unintended effects) as they become more capable, strong, and wise.

The thing about using power and control is that it requires external force to make sure children are behaving the way we think they should. We constantly need to micromanage behaviour, which does little to actually develop the child’s own internal compass and capacity to navigate more complicated situations as they get older, and so we set ourselves up to continue playing this role. The main strategies require using yelling, threats, and punishments to incite fear in the child to do what we have told them to do. Even something as simple as counting (you better be in the house by the time I get to three!) can fuel uncertainty and fear in a child, because what’s going to happen when you get to three?

If you find yourself stuck in power struggles with the children you love, friend, you’re not alone. We are the posterity of generations that deemed children unworthy of a voice, demanded obedience regardless of the child’s own internal state and needs, and believed that too much affection would create spoiled brats (spoiler alert: affection actually builds a child’s brain). Many of us remember how unfair and painful it felt to be dismissed by our parents and other caregivers, and yet we struggle to do something different, though not for lack of trying. I see you—I know you must be exhausted, and I’m holding space for the parts of you that have been wounded and are still showing up in the best way you know how.

Thankfully, I don’t think the options are ‘Control vs. No Control;’ I would say it’s more like ‘Control vs. Influence.’ At the start of my career, I found it really challenging to move toward using my influence to encourage cooperation because it meant putting a child’s power on an equal plane as me—which I’m sure sometimes looked as though I had no control. And to be honest, this way of working with children demands more from me in the beginning: it requires me to pause longer, to reflect more, to be a safe container for the child’s emotions, and to suspend being right in order to consider the child’s wants/needs/opinions. It requires coaching children, over and over (and over) again, until they have the capacity and tools to manage their behaviour on their own. Most of all, it requires me to view the child as a partner in this relationship and trust that they innately want what is good and kind, for themselves and others, even if they don’t know how to achieve that (yet).

But the time it takes is vastly, vastly, outweighed by the joy that comes from seeing children thrive and become caring, capable little beings.

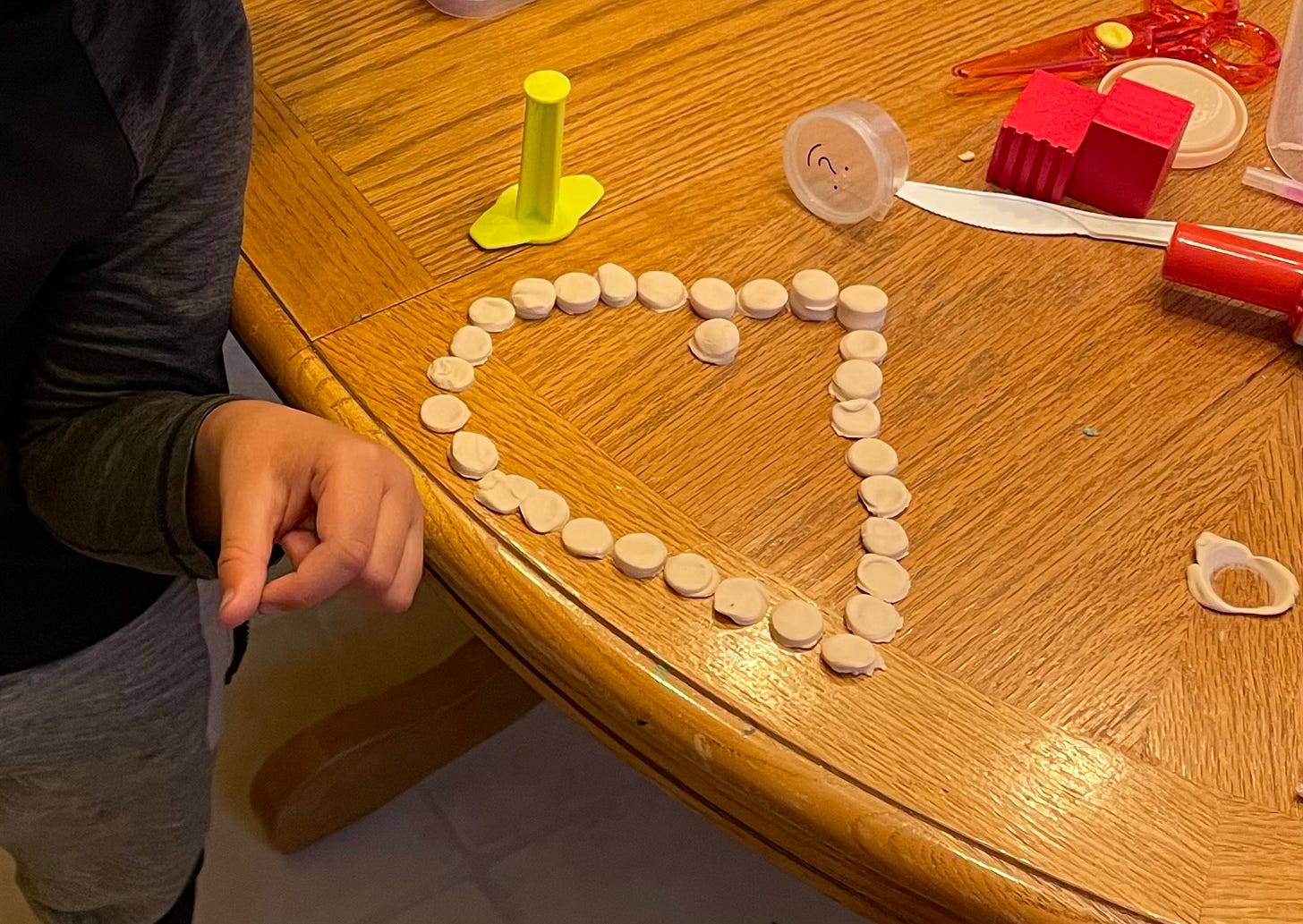

After seriously considering my options, raising my voice (and subsequently apologizing) more than I ever had before, and revisiting my strategies on multiple occasions, I started to see a shift in the way this child was showing up. Rather than get defensive when another child was upset (I didn’t do it!), they got curious and asked why they were crying. They were engaging in more complicated play scenarios with the other kids, working collaboratively to come up with ideas and solve problems. I even started to see their creative side come out as they began to feel more safe in my care and better able to move through their frustrations. They started to believe that I would hear them, do my best to meet their underlying needs, and work together to find suitable solutions.

I’ve never worked harder to use my influence to encourage cooperation.

And it was totally worth it.

When was the last time fear of punishment motivated you to do something kind? What feelings did it produce for you as a result?

Do you believe that the children you love generally have good intentions?

When a child is ‘misbehaving,’ what would happen if you stopped and asked yourself what needs they are trying to meet?

"Do you believe that the children you love generally have good intentions?" 🔥 such a game changing question. I started believing they do years before I had kids, but I still have to remind myself after years of messaging telling me that kids were trying to be defiant every time their behaviour feels difficult.